The ICOS network was founded in a little more than a decade ago, but many of its measurement stations have served scientists long before this. Long-term greenhouse gas measurements are needed to analyse both long-term climatic trends and extreme events.

The ICOS network of greenhouse gas measurement consists of around 180 stations throughout Europe. Together, their data forms an overview of the carbon cycle in Europe, covering atmospheric, ecosystem and ocean measurements.

Before ICOS, measurement stations were operated independently by their host institutes, often relying on short-term project funding. European projects such as CHIOTTO and CarboEurope played an important role in the development of these stations, but it was soon recognised that these observations needed a more stable structure. Project funding made greenhouse gas observations more vulnerable to observation gaps.

“Being dependent on short-term projects was a threat for the observations, as funding gaps were common and had to be covered by host institutes. This caused major headaches for researchers and managers, who had to keep things running on a shoestring until the next project opportunity appeared. In the meantime, people had to look for other job opportunities, leading to losses in experience and know-how, and it was also hard to maintain the required quality of the observations”, Dr Alex Vermeulen, Director of the ICOS Carbon Portal says.

In 2006, European scientists and their national support networks combined their efforts and initiated the ICOS RI, the Integrated Carbon Observation System Research Infrastructure. In 2015, it gained the legal status of an ERIC, European Research Infrastructure Consortium. Through the ERIC framework, each ICOS member state now commits to supporting high quality operation of stations over a long period.

“To be sure that the trends we report are truly linked to the causes we are studying, we need long time series of data. The longer the record, the more confidently we can separate natural variation from long-term change,” says Dr Elena Saltikoff, Head of Operations at ICOS ERIC.

Quality greenhouse gas data from all across Europe

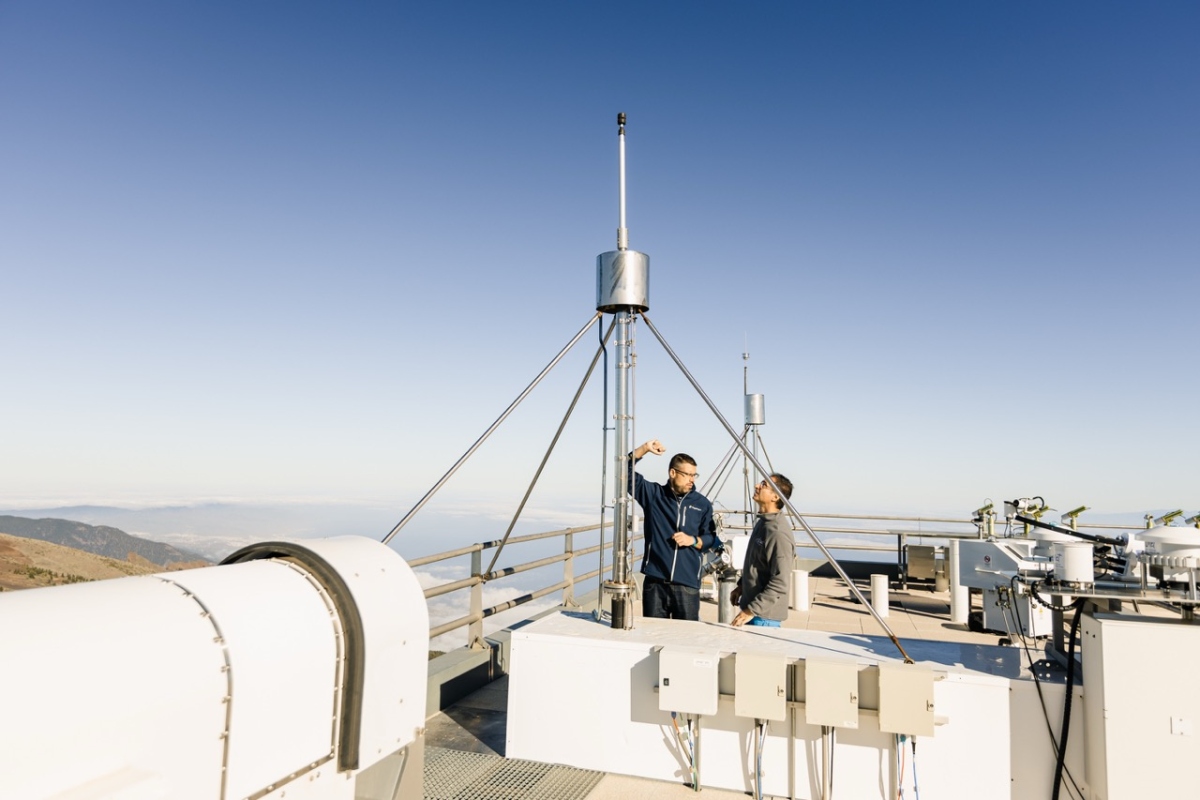

Some of Europe’s longest-running atmospheric stations are now a part of ICOS. The atmospheric stations with some of the longest records of greenhouse gas measurements are Schauinsland, Germany (since 1972), Izaña, Spain (since 1984), Mace Head, Ireland (since 1992), Cabauw, the Netherlands (since 1992), Hegyhatsal, Hungary (since 1993), and Heidelberg, Germany (since 1996). If weather observations are included, Hohenpeissenberg in Germany holds the record for the longest continuous measurements, beginning in 1781.

On the ecosystem side, systematic greenhouse gas measurements in Europe started somewhere around the mid-1990’s. The first ICOS labelled ecosystem stations in the ICOS records of labelled stations were Lonzee in Belgium, Torgnon in Italy and Siikaneva in Finland, all three in November 2017. The first atmosphere stations in the ICOS records Hyytiälä. Finland, Observatoire pérenne de l'environnement in France and Gartow in Germany, were also added to the ICOS records on that date.

The ocean part of the ICOS network is a vital one, as the ocean absorbs about a quarter of human carbon dioxide emissions. The first labelled ICOS station was Tukuma Arctica in May 2018. Systematic surface ocean carbon measurements started earlier, mainly through the SOCAT database which was formally initiated from 2007.

“In the early years of ICOS the members of our community agreed and documented detailed protocols. Thanks to them, we can be sure that all the observations are made in the same way, which allows us to compare different years and different locations, and to trust that the differences come from the environment, not the methods,” Elena Saltikoff describes.

ICOS is a standard-maker in greenhouse gas measurements

Throughout the years, ICOS has developed a strong set of shared protocols and standards. Today, stations go through a labelling process to ensure they meet strict requirements, guaranteeing that data are both reliable and comparable. This unique labelling process makes ICOS a standard-maker globally, actively developing new procedures and protocols, while also aligning with global frameworks such as the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the Surface Ocean CO₂ Atlas (SOCAT).

Both Elena Saltikoff and Alex Vermeulen cite ICOS’s Monitoring Station Assemblies (MSAs) as a vital part of this standard-making process.

“The Principal Investigators of our stations in each domain bring wide experience, for example from different climates. They participate in Monitoring Station Assemblies, where new protocols are actively discussed between the central facilities and the station PIs,” Elena Saltikoff says.

Together, ICOS facilities and the Monitoring Station Assemblies develop measurement protocols and continuously evaluate the measurement quality of the network. This interaction makes ICOS a unique organisation.

“As most station managers are themselves heavily involved in the underlying science, we make sure that the observations fulfill the needs of the users who analyse the data, and that the strategy and implementation are feasible, workable and cost-effective,” Vermeulen says.

The strength of ICOS lies in linking the atmosphere, ecosystems and oceans. By connecting these domains, scientists can trace carbon as it moves through the Earth system, test models against observations, and provide robust data for governments to use in climate reporting. Long-term, standardised measurements make it possible to transform scattered observations into a coherent picture of the carbon cycle.

“Greenhouse gases spread all over the globe and don’t care about borders. A molecule emitted in Luxembourg has the same impact as one from tropical Africa or Amazonia. To manage and track and control the climate warming by greenhouse gases we will need a better global coverage of the measurements with the right high quality and long-term commitment”, Alex Vermeulen concludes.